After a health crisis that had him “scared? s***less,” the $90 million radio personality opens up about retirement, Trump, and his personal and professional metamorphosis: “I’d feel really f***ing s***ty if I hadn’t evolved.”

On Wednesday, May 10, 2017, for the first time in memory, Howard Stern abruptly canceled that day’s show. His listeners, a famously loyal subset of SiriusXM’s 36 million subscribers who’ve made the boundary-pushing “shock jock” a part of their lives since he rose to prominence in the ’80s, were understandably alarmed.

Reddit lit up with crackpot theories, and a handful of dogged reporters tracked down the host’s elderly parents to check up on him.

By Monday, the self-described king of all media was back on the radio, poking fun at the hullaballoo, as many hoped he would. It was just the flu, he told his audience: “Why is it such a big deal that I took a fucking day off?”

Turns out, he was lying through his teeth.

On the morning in question, Stern wasn’t home with a fever or runny nose; he was being carted into surgery. For the better part of the previous year, he’d been shuttling between appointments as doctors monitored a low white blood cell count revealed during a routine checkup and, later, discovered a growth on his kidney. The chance that it was cancerous: 90 percent.

For a man who lives his life on-air, divulging such personal details as his first wife’s miscarriage and his reputedly undersized penis, he’d been uncharacteristically discreet about his latest struggle.

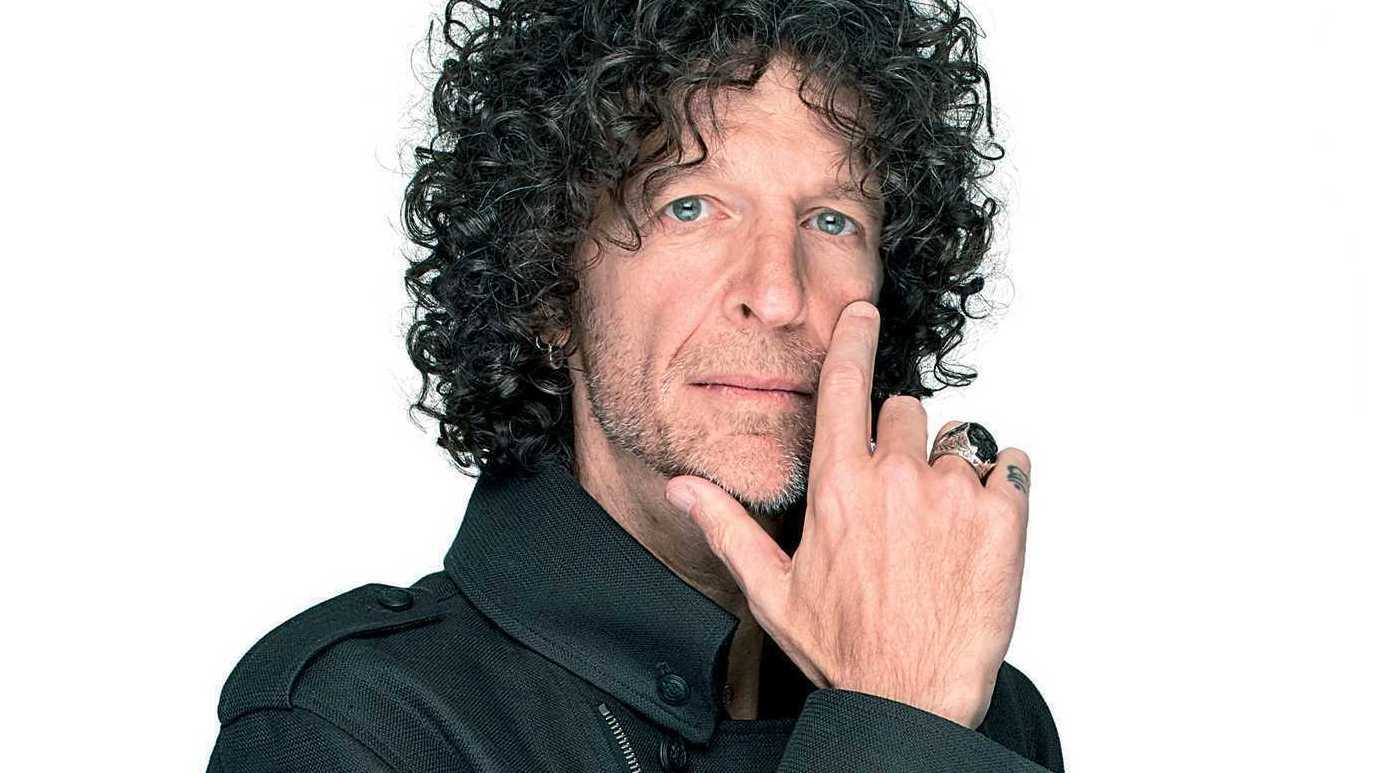

He told only his very inner circle, a group that included his second wife, Beth, his three daughters, his therapist, and his on-air foil of nearly four decades, Robin Quivers, herself a cancer survivor. Until all this, Stern had considered himself invincible — at 65, his 6-foot-5 frame was still enviably trim, his head endowed with a thick mop of curls. He ate well and exercised often. Cancer was a ridiculous notion.

“And now all I’m thinking is, ‘I’m going to die,’ ” he recalls in an interview, his first time discussing the health issue publicly. “And I’m scared shitless.”

A couple of hours and seven incisions to his abdomen later, he came out of surgery to learn it had all been a scare. A tiny, harmless cyst. The news should have been comforting. But for the first time in Stern’s adult life, he’d come face-to-face with his mortality, and now there was no turning back.

In the 24 months since, he’s found himself wondering often if he’s done it all wrong. Despite amassing fame and fortune unrivaled in his medium, Stern says he’s a mountain of regret.

He beats himself up over the father he couldn’t be to those three girls, now grown and living elsewhere; and the husband he never was to their mother, Alison, who finally left him in 1999. He can’t read his first two best-selling books, Private Parts (1993) and Miss America (’95), without cringing at his narcissism, and he insists nearly every one of the interviews he conducted during his pre-satellite radio days makes him sick.

“I was so completely fucked up back then,” he says, his head shaking with disgust on this morning in early April. “I didn’t know what was up and what was down, and there was no room for anybody else on the planet.” His more recent metamorphosis, the result of age, a healthy marriage, and intensive therapy, has revealed sensitivities he didn’t know he had. It’s also sharpened his skills as an interviewer.

Dressed now like an aging rocker with a pair of dark jeans, boots, and his signature shades perched just above his brows, Stern is sprawled out on the charcoal-gray couch usually reserved for guests in his midtown Manhattan studio.

He’s explaining how his brush with cancer is a key reason he agreed to write his first book in two decades, Howard Stern Comes Again, a curated collection of edited transcripts from his favorite interviews — with everyone from Billy Joel to Donald Trump (more on him later) — wrapped in his own memories and candid self-reflection. There’s considerably more in the book on his health scare, too, along with his musings on fame, sex, and spirituality.

“It’s as much his autobiography in conversation as it is a tour through American pop culture over the last 20 years,” says Jonathan Karp, publisher of Simon & Schuster, which will release the book on May 14. That brush is also the reason Stern’s been having real discussions about what’s next once his contract with SiriusXM, which reportedly pays him $90 million a year, expires at the end of 2020.

“I’m at a place now where I am trying to figure out how to spend the rest of my life, however long that might be,” he says. He’s been flirting with the idea of retirement in conversation with close friends and, occasionally, on the air. “It seems weird to me not to have this,” he nods at the desk where he spends four to five hours three mornings a week — but maybe it would be great. Maybe his painting could improve. Maybe he could take that sketch class he’s been thinking about. Maybe he and Beth, 46, and their coterie of rescue cats could travel more, visiting those kids he doesn’t get to see enough of.

He wouldn’t be bored, he’s sure of that; but is Howard Stern ready to shut up?

America’s most recognizable radio personality has been screaming for attention his entire life. Early on, it was through performance: dirty puppet shows for his pals, impressions for his parents. His radio engineer father would offer feedback, if not exactly encouragement — and a valuable lesson in how to keep an audience engaged. “Stop!” his dad would bark. “You’re going on too long! Make it interesting!”

By the time he hit puberty, Howard’s Long Island community had transformed from predominantly white to predominantly black. As he recalls, the arrival of black families prompted his so-called liberal neighbors to flee in the middle of the night. It was an early education in hypocrisy, and it left him outraged:

“All these preachy phonies who would go to services and say, ‘All people are the same in God’s eyes’ were full of shit,” he seethes. His parents, along with Stern and his older sister, Ellen, would stay put. By his freshman year of high school, he was one of only a handful of white kids left in class, a de facto outsider who’d frequently find himself on the receiving end of somebody’s fist.

The Sterns eventually relocated to a nearby white neighborhood, but by then Howard was woefully behind academically and a complete disaster socially.

“I was traumatized,” he says. Still, he got admitted to Boston University, where he found an outlet on the campus radio station and later a series of gigs that took him from Hartford to Detroit. In the early days, he’d shake every time he got on-air; but with time, he began to relax and find his voice, a mix of hijinks and puerile humor.

By the early ’80s, Stern landed in D.C., where he was first paired with Quivers and, through a series of outrageous antics, sealed his shock jock reputation. No prank seemed to get quite as much attention as the one he pulled the morning after an Air Florida flight crashed in the Potomac River, killing 78 people.

The host famously pretended to ring the airline, inquiring about the price of a one-way ticket to the 14th Street Bridge. Those who weren’t horrified were highly amused. From there, Stern moved to New York, the most coveted of markets, where he shared with format predecessor Don Imus a station and a slogan: “If we weren’t so bad, we wouldn’t be so good.” By 1986, his eponymous show was nationally syndicated.

With each stunt, Stern’s audience seemed to grow larger and more passionate. At its peak, The Howard Stern Show reached an estimated 20 million weekly listeners. Money followed though the number of zeroes seemed important to him largely as a measure of success. Save a few pricey homes — in Manhattan, the Hamptons, and Florida — the borderline recluse has never been known as a big spender or a man of lavish taste.

(Money is the rare subject that Stern has long been unwilling to touch, unless of course, he’s the one asking the questions.) Winning, on the other hand, “became an almost debilitating obsession,” he says. He was committed to doing and saying pretty much anything to stay on top:

be it dialing for dates with lesbians or banging bare bottoms like bongos. At one point, one in every four cars on Long Island was listening to The Howard Stern Show during the morning commute; he was fixated on the other three: What the hell were they listening to if not him?

For years, guests served merely as props, there to service Stern’s audience. “My interviewing technique was like bashing someone in the face with a sledgehammer,” he writes in the new book.

“I was like the Joker, and all I wanted to do was cause chaos.” He asked Gilda Radner if Gene Wilder was well endowed, driving her right out of the studio. He spent the bulk of his time with Carly Simon telling the singer how hot she was; and, despite multiple warnings not to ask George Michael about his sexuality, he did so immediately. There were plenty more, from Eminem to Will Ferrell, who appeared once and then never again.

What Stern lacked was the humility to be a fan of anybody but himself. At least not publicly. “I lashed out at anyone and everyone whose career was prospering,” he offers. “I thought I should be at the center of the universe, and whenever it seemed like someone else was, I couldn’t accept it.”

David Letterman? Blasted him. Jerry Seinfeld? Him, too. Rosie O’Donnell? Forget it. His denunciations of her inspired Stern fans to rummage through her trash and threaten the life of her young son. “It got to the point where it was terrifying,” says O’Donnell, who, in a stunning twist, became a Stern confidante years later.

An early ’90s interview he did with Robin Williams still ranks among Stern’s biggest regrets, however, in part because it’s too late to apologize, as he has to others.

“I loved Robin Williams, but there I am beating him over the head with, like, ‘Hey, I hear you’re fucking your nanny?’ I could have had a great conversation, but I’m playing to the audience,” he says. “They want to hear outrageousness, and that’s my arrogance thinking that Robin Williams can’t entertain my audience. How stupid am I?”

Over time, Stern found himself stuck in an arms race with himself, constantly reaching for new levels of outrage. It caused endless headaches: Religious groups came after him, as did the FCC, levying millions in fines.

Advertisers regularly pulled their support and cranks called in death threats. “I was a nervous fucking wreck, ready to jump out a window,” he admits. But he wouldn’t be stopped. “Every issue — race, religion, sexuality — was dealt with as honestly and openly as possible to the detriment of everything around me. I was like scorched earth, … trying to be heard like the mountain that roared.”

Everything else in Stern’s life, including his college sweetheart, Alison, and their three daughters, took a back seat. He just couldn’t see it at the time. “I lived in a delusional world. I thought I was the best parent. I thought I was like Ward Cleaver, living the Leave It to Beaver life. I didn’t realize everything was crumbling around me,” he says now. “I mean, I didn’t even know what it meant to be a grown man with a family. I didn’t know anything. I was a child.”

Then, in late 2004, came a lifeline from Sirius, a fledgling satellite service that was willing to bet $500 million (and, arguably, its future) on Stern. He’d start in 2006, getting two entire channels to himself and the freedom to do and say whatever he damn well pleased.

No federal decency rules to contend with, nor skittish bosses breathing down his neck. On his way out, he caused one last firestorm, promoting his switch to Sirius on the air at CBS Radio, prompting then-boss Leslie Moonves to slap him with a nine-figure lawsuit. Scorched earth it was.

Sirius was, by all accounts, the Wild West. He could get away with anything, and for a good stretch, he did. “We said ‘fuck,’ we said ‘shit,’ we weighed a guy’s doody,” he recalls. Then something happened. He began to lose interest in outrage. With no rules left to break, it wasn’t that much fun anymore.

It was time to evolve.

By that point, Stern was spending as many as four days a week in therapy — he’s now down to two, though his longtime therapist would prefer three — and he was interested in having more genuine conversations. He felt he was finally being heard and was eager to hear from others. “You can only interview so many strippers,” he offers without a whiff of irony. Don’t get him wrong, however: he “loved the idea that we’d go on the air and measure our penises or discuss vaginal secretions —whatever it was, if it freaked you out, I loved it because, to me, it was not a big deal. But now I find it gross. And I’d feel fucking shitty if I hadn’t evolved. I’d be completely out of step with the times.”

With little warning, Stern’s off on a tear about the industry’s more recent cultural reckoning, enraged once again by the hypocrisy it’s revealed. After all, several of the professional moralists who’d attacked him for his on-air antics were now being exposed for “doing really weird shit” in private. “It just shows you that people are full of shit,” he says, before directing his fury at his former nemesis: “I’ll admit there was a certain joy that I took when the #MeToo movement broke and [we found out] Les Moonves is doing all these things in his private life.”

To Stern’s delight, most of his listeners have been willing to evolve with him. Not all, of course. Some miss the old Howard — including former Howard Stern Show personality Artie Lange — who accuse him of having gone soft. Stern, for his part, counters that he has little left to offer those who say, “We want you squeezing a perfect stranger’s titties in the studio.”

Which is not to suggest he or his show has somehow become G-rated. There are still plenty of pranks, profanity, and egregious sex talk that can occasionally feel jarring in the year 2019. He shrugs and says, “I still have a juvenile sense of humor.”

At his therapist’s urging, Stern has been making room in his life for interests beyond radio. He took up chess for a few years, then photography, though in both cases, he says, “My compulsion to be the greatest crept in and strangled the fun out of it.” Now, he’s all in on painting. He’s opened himself up to genuine friendships, too, with folks like Jimmy Kimmel and O’Donnell.

(It was Mia Farrow who brokered peace between the two, telling Stern that he and Rosie had been the only ones who publicly admonished her ex, Woody Allen, well before it was culturally in vogue to do so. “She told him, ‘Stop being such an asshole. You and Rosie have more in common than you think,’ ” says O’Donnell. “And really, we do.”)

Selling Hollywood’s gatekeepers on the new Stern would take time. For years, he’d been enemy No. 1 in most publicity circles, and often the feeling was mutual. “Their job was to avoid controversy,” he says, “and my job was to create it.

” But, gradually, he became so eager to showcase his softer side, that he signed on to judge America’s Got Talent in 2012, to the shock of his longtime agent, Don Buchwald. Perhaps more shocking: It worked. “I had a reputation as a stark-raving lunatic before that,” says Stern. After his four seasons on the NBC talent competition, “I went from America’s Nightmare to Santa Claus. People were putting their kids on my lap.”

Slowly, stars and their handlers began to accept the shift, too. Stern describes his interviewing technique now as the “dinner party approach,” explaining how he coaxes his guests to be spontaneous without having to get in their faces.

He points to an early 2015 interview with Gwyneth Paltrow that weaved its way from a discussion of relationships to one of oral sex as a major turning point. “Had I said to her, ‘Gwyneth Paltrow, do you blow your husband?’ I’m an asshole,” he says. “But, sure enough, we start talking, and she’s fascinating, and I’m getting to know her, and then she goes: ‘One of the things you can do to make your man happy, ladies, is, like, sometimes in the middle of a fight, I just blow him. It ends everything.’ So, she took me there.”

Stern’s longtime producer, Gary “Baba Booey” Dell’Abate, has called the Paltrow interview “one of the most important milestones” for his job as a booker. In the years since Stern’s couch has become a sought-after stop on the publicity tour for a wide swath of Hollywood’s A-list — though flacks still cop to sweating through clients’ hour-plus interviews, which quickly evolve past prepackaged sound bites to become intimate character excavations. “When you talk to Howard, you just kind of explode with candor,” says Lena Dunham, whose relationship with Stern got off to a rocky start in early 2013 when he described her as “a little fat girl who looks like Jonah Hill.” He later apologized, declared himself a major Girls fan, and invited her on to dig deep on subjects ranging from obsessive-compulsive disorder, from which they both suffer, to sexual assault. Adds Dunham, “I wish the side effect [of going on his show] wasn’t tons of aggressive headlines, because while it’s happening it feels really good.”

Kimmel, a loyal listener long before he became a close friend, considers Stern the best the format has to offer, and he’s hardly unique in his assessment. “Unlike the late-night talk shows, nothing is off-limits on his show, and you know that going in,” says Kimmel, having been a guest himself more than 30 times. “If you put limits on the interview, Howard won’t do it. No matter how tempting or how much he wants the guest, he just won’t. So, if you’re Paul McCartney and you want to publicize something, you know you’re going to sit with Howard for an hour and a half and talk about whatever Howard wants to talk about, and no one is above that.”

Curating a book of Stern’s best interviews was supposed to be simple. Jonathan Karp had assured him that Simon & Schuster would do nearly all of the work. In fact, when Karp arrived at Stern’s Manhattan apartment in April 2017, the publisher had 30 transcripts of his most popular interviews already bound with a book jacket. All Stern would have to do was write a few words of introduction. He was flattered enough to say yes.

Like every other major publisher, Karp had been courting Stern for years for the express reason that his base had proved eager book buyers, as evidenced by the performance of his first two tomes. When Private Parts came out in 1993, it was the fastest seller in Simon & Schuster’s history. Beatles-esque hysteria at book signings and, later, a film adaptation with Stern as its star, followed. His second, Miss America, managed to outdo it, becoming what was, at the time, the fastest seller in publishing history.

But Stern didn’t love the idea of doing a third. Books were simply too much work, he’d often say, which is why Karp tried to make it easy. Of course, Stern was constitutionally incapable of doing it that way. He couldn’t let someone else pick the interviews; he’d have to do that himself. So a one-year project took two, as he pored over hundreds of transcripts and decided to write an intimate introduction for everyone he chose. Ultimately, he settled on close to 40 in-depth conversations, from the early and uncomfortable (Bill O’Reilly) to the more recent and evolved (Bill Murray); along with several dozen snippets that he’d weave together by theme, like sex and relationships or money and fame.

Then came another idea: He’d lace throughout the book a sampling of his 40-plus conversations with Trump, beginning with a 1995 exchange in which they joke about a presidential run; he’d also devote at least a few pages to the interview he tried desperately to land with Hillary Clinton, who, he’d reveal, had rebuffed him at every turn. Despite the host’s history with the current president, who’d regularly call in and discuss such subjects as his sex life with Melania or his daughter Ivanka’s “very voluptuous” breasts, Stern was an ardent supporter of Clinton, both in 2008 and again in 2016. Still, he says he saw before others how tough it would be for her to beat Trump.

His listeners span the country, he explains, and in that final stretch, he could see that Hillary wasn’t connecting with them. Stern isn’t arrogant enough to say for sure that an interview on his show could have tipped the election in her favor, but he doesn’t rule it out, either. “There’s a segment of my audience that really gets turned on to people they thought they hated because we tap into their humanity,” he says, rattling off examples like Lady Gaga. “They were like, ‘Fuck Lady Gaga, why are you having her on?’ And then it’s over, and they go, ‘Shit man, I’m going to go see her in concert.’ ”

For a while there, Stern says his wife would get annoyed every time a conversation turned to the election since it always seemed to play out the same way. He’d ask those better versed in politics than he who they thought would win and he’d refuse to bite his tongue when inevitably he’d be told Hillary. “I’d sit there at these dinner parties and go, ‘Not that you asked, but I don’t think you’re seeing this the right way,’ ” he says. ” ‘Donald is communicating. He’s talking like a dude. That’s very powerful — take it from someone who knows.’ ” Lest anyone forget, Stern soared in the polls when he ran for governor of New York on the libertarian ticket in 1994, and all he had to say was, “We’re going to kill all the criminals, take their crispy remains and stick them in the potholes.” He removed himself from the race before it was too late.

On-air and off, he had tried to get Trump to do the same. Early on, Stern was still fielding his calls from the campaign trail and spending time at Mar-a-Lago. Sure, he considered Trump among his greatest all-time radio guests — raw and unfiltered — but the leader of the free world? He insists in those days, he never imagined Trump would get anywhere near that far, and he’s convinced Trump didn’t either. Save for a brief congratulatory exchange when Trump won, the two haven’t had any interaction since Stern declined his request to speak at the Republican National Convention. “It was a difficult thing because there’s a part of me that really likes Donald, but I just don’t agree politically,” he says. Still, he jokes: “A more self-serving person would have gone all in on Donald because I’d probably be the FCC commissioner or a Supreme Court justice by now.”

The rest of Stern’s book can occasionally read like a series of love letters to his subjects. Before a Kimmel interview, he writes about how his friend is often there to provide him with a boost of confidence when he needs it most — and for that, he shares, “I love him”; before one with O’Donnell, he offers: “I remember thinking, ‘How could I have missed out in my life on someone so special because of some dumb posturing on the radio?’ ” He hopes that the collection, as a whole, adequately captures his evolution and ultimately becomes his legacy; at the very least, he says, it’s how he wants to present himself to his daughters. Just don’t, under any circumstance, accuse Stern of having lost his edge.

It’s a lesson that talk show host Wendy Williams learned the hard way. After praising him as her role model and his book as an inevitable best-seller — per Karp, it’s Simon & Schuster’s fastest seller of the year, in terms of pre-orders — she became the latest to suggest the host had gone soft. “He’s a Hollywood insider now,” Williams said on a March episode of her show, “which sucks because you started to like me, being of the people, but at some point, you sat behind that microphone for too long, and now you are the people.”

Within hours, Stern had fired back, eviscerating Williams on his air. “Jealous bitch. … You’ll never be me,” he fumed. “You don’t have my wit and you don’t have my talent.” Weeks later, he regrets the tirade, acknowledging: “That was me at my worst. I thought she was saying that I was a piece of shit and I sucked. But as [I hear it] now, I don’t see it as an offense at all. If ‘Hollywood’ means that I’ve evolved in some way and the show has changed, then yeah, she hit the nail on the head.” He’s pulled the rant from rerun airings.

Soon, the conversation comes back around to his health scare and with it his musings about a future off the radio. Of course, Stern has contemplated walking away before, notably in the run-up to his last contract negotiation, only to re-up with a rich new deal in 2015. Similar talks will reignite in the next year, if not sooner, along with an almost inevitable crush of headlines that will ask whether Howard Stern is still worth $90 million a year. Sure, some will argue, when he signed his first pact in 2004, he was key to the future of what was then just Sirius, with its 1.1 million subscribers and $67 million in revenue. On his back, the company, which later merged with XM Satellite Radio, built both its brand and its base.

By 2014, however, the last time Macquarie Securities analyst Amy Yong surveyed SiriusXM subscribers, only 12 percent (or about 3.2 million listeners) were tuning in to Stern, and only 5 percent said they’d bail if he left. And now? Yong cites SiriusXM’s subscriber growth, currently at 36 million, and its recent $3.5 billion acquisition of Pandora: “They’re in such a different life stage, and they’ve done a really good job of diversifying,” she says of a company that now boasts $5.8 billion in revenue. “They have like 150 channels, so no one is going to have that much leverage.”

And maybe it’s just as well. Stern’s been spending a lot more of his time “thinking about the hourglass,” he says, “and the sand emptying.” He daydreams about the next chapter when he’ll wake up, read the paper, and paint for hours at a time. Still, it’s hard to imagine the guy who regularly sneaks onto Twitter to gauge listener reactions is ready to hang it all up. His eyes, which have been darting around the studio for the past hour and a half, suddenly settle on the microphone hanging high above his desk: “To walk away from what I’m good at?” he says, questioning himself already. “I don’t even know that I have it 100 percent right yet. And maybe there’s more to explore …”

Leave a Reply